Since the dawn of surfing, the west coast of the United States has been considered a cultural root that helped establish and propel surfing into the public limelight, embedding a distinct lifestyle and mentality into the communities that occupy its beautiful coastline. Although California practically needs no introduction, proving itself day-in and day-out of its caliber of surfing dominance and prestige, in 2018 California declared surfing its official state sport, heightening its social recognition and cultural distinction. While California does receive most of the credit and stardom as the surfing hub of the west coast, Oregon and Washington are arguably more emblematic of a true surfer’s paradise. As with most exploits that are more difficult or less attainable, they are often more rewarding. Oregon and Washington are faultless examples of this: jagged rock cliffs, limited feasible access, frigid water making for fewer crowds, miles-and-miles of uninhabited coastline, and pristine landscapes vacant from the pollution of coastal mansions and overly condensed towns.

Together, California, Oregon, and Washington make up over 1500 miles of Pacific coastline… And under the right conditions, this surfer’s paradise also makes for incredible kiting. Although surfers and kiters respect the wind in a contrasting paradigm, the direction and its presence play an extensive role in the conditions that transpire and the activity that takes place. When the preferred conditions for surfers deteriorate, typically fantastic kiting conditions emerge. In an attempt to seize both ends of this spectrum – hoping for offshore or minimal winds for surfing, accompanied by a healthy mix of side-shore winds for kiting – Noè, myself and acclaimed photographer and friend, Toby Bromwich, plotted a trip and packed our bags. We planned to begin our journey in San Francisco, California, making our way north, following the coast and taking advantage of every day, with or without wind.

The reason many stereotypes and clichés exist is often because they are true. This is why many travel to Brazil during the fall and South Africa during the winter, almost certain to take advantage of its stereotypical consistency, providing wind in seemingly limitless abundance. With kiting, when assessing a destination worth traveling, one that is capable of providing and that consistently provides are two elemental qualities that fundamentally impact the likelihood of a trip coming to fruition. The unfortunate reality of the west coast is that for most of the year it is capable of providing incredible kiting conditions, but relying on it for wind is impractical. This gave Noè and me the opportunity to create, and with the help of Toby, expose a trip that was unpredictable and distinct to our vision as we had to work within the confines of the conditions we encountered.

To maximize our chances of scoring, we figured the most authentic way to immerse ourselves was to follow the forecasts, rely on a pickup truck for transportation, and pitch a tent in locations that allowed easy access to the ocean. Although camping to exploit a specific venture is nothing new, often precipitated by enthusiasts, professionals, and zealous vagabonds, camping while doing activities such as kiting has changed dramatically. Over the last decade, a large portion of the world, especially the US west coast, has experienced a rapid influx in the presence of personal utility vans, which haul with them tools to experience, as opposed to tools for assistance. These vans are homes on wheels, furnished to the brim, and capable of long-term relocation with a simple push to the gas pedal. They are small enough to fit in a parking spot, but large enough to be an eyesore and an irrefutable distinction of someone in transit, attempting to clinch a west coast experience. For those yet to experience it, this portion of the US is an epicenter for transplants and visitors, desperate to immerse themselves in this paradise.

In planning, Noè and I had envisioned spending a large chunk of our trip in northern California, but after arriving, the forecast drove us elsewhere as the wind charts were on a downward trend and with no foreseeable sign of swell. Without wasting any time, we revised our plans and hit the road, making our first stop just south of the Oregon border, surrounded by Redwoods, some of the largest and tallest trees in the world with trunks so large it makes one feel insignificant amidst their presence. The beaches shared similar significance with coarse rock cliffs jetting into the water, acting as a barrier against the waves that ceaselessly lap against them. Many nights we pitched our tent mere yards from the ocean towards the top of dunes, falling asleep to the churn of the ocean and waking up to the light of the sun.

While California more readily caters to the amusement of travelers, the further north we drove, the further we removed ourselves from the cliché glamor illustrated by blogs and ‘van life’ that permeates the internet. As we exited California, the more we were able to distinguish the transformation of the coastline and the towns that abut it. Although it was early September, and we had high hopes of camping in the summer warmth, Oregon’s coast is a stark reminder of the brisk conditions that can ward off those timid by cool ocean air and frigid water temps. During the evenings when the sun is swallowed by the ocean, Noè and I found ourselves seeking full insulating attire: winter beanies and down jackets, and excited to regain comfortable circulation from our sleeping bags. One of the great perks of sleeping near the ocean is the unmatched scenery and proximity to the location if conditions align. However, one of the downsides of sleeping on the coast is the humidity, especially in colder weather. Nearly every morning our tent would be pooled with condensation, and our sleeping bags acted as a sponge that slowly absorbed the moisture through the night. Fortunately, we never experienced rain, and during the day we would lay our gear out in the sun to dry, as a preparatory reset for the night to come.

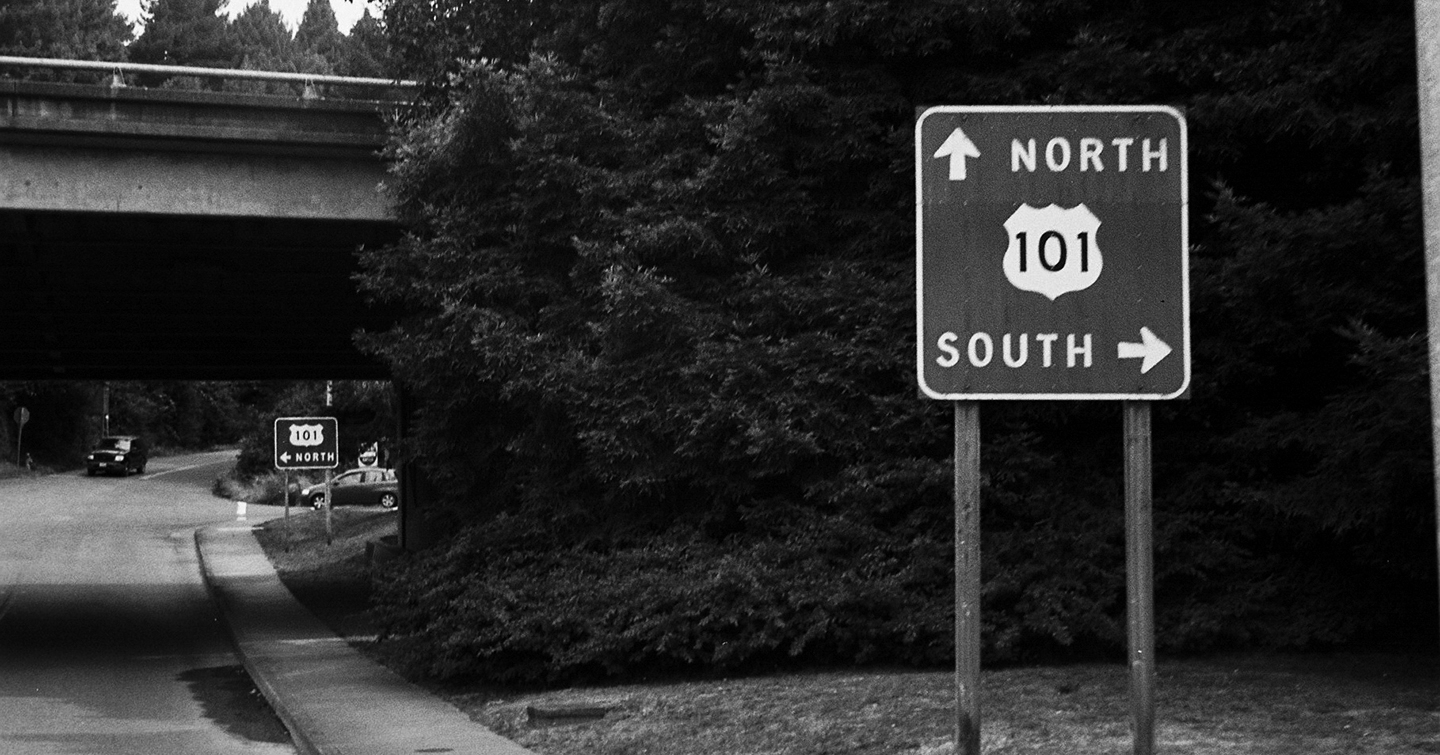

Beyond the intricacies of camping, the trip itself was exhausting. We were constantly on the move and doing our best to take advantage of the wind, which was more of a light and inconsistent sea breeze, allowing us to do some forced field testing on the lightwind range, which did not disappoint. While it materialized the trip was an accelerated blur, and it wasn’t until after the fact that I was able to digest all that had transpired. As with most trips I am always left wishing it could have been longer or that we could have done more, but for the amount of ground we were able to cover, the locations we were able to ride, and the world-class real estate we were able to pitch our tents beside, our time navigating Route 101 more than fulfilled the expectations of our venture.

At nearly every spot that we pumped up our kites we were the only ones kiting, giving credence to the novelty of each location and adding value to our trip. Even if the wind had been completely nonexistent the trip would not have been a wash, but we would have lugged a trunkful of gear around much of the western coast unnecessarily. A crucial factor that can dictate the experience associated with a trip such as this is the people you meet along the way. The passersby that greeted us provided us with great amusement and bewildered fascination. Never once was there a dull moment. Noè was able to paraglide below a lighthouse, and just beyond him we saw whales navigate their way through kelp forests. We drove our truck through a hole in a tree (purposefully), toasted bagels over a stovetop, Jetboiled excessive amounts of tea and coffee, cooked gourmet pizza on the side of the road, and made our way into the ocean at least once every day. What more could you ask for?

All in, the trip was an incredible experience and offered us an opportunity to gain an appreciation for the west coast and its haphazard forecasts; sometimes wind blowing from the opposite direction indicated by the meters, and on one occasion, its variability allowing us to kite in two completely opposite directions in the matter of an hour. With confidence, I stake the claim that when given the opportunity to kite on the west coast, never sleep when conditions materialize because they can disappear as quickly as they arrive and may never return! For the entirety of the trip, we would either ride until nightfall or stay at the water’s edge long enough to wear out our optimism for the conditions to swing in our favor. As a result, if we weren’t attempting to cook, we were scrambling to find a restaurant willing to serve us past 9pm, which proved exceedingly difficult in the small coastal towns we found ourselves passing through.

This was not my first road trip with Noè and certainly will not be my last. However, it will be a memorable one. I will remember it as a trip where sleep was minimal, forecasts were defective, sustenance was irrelevant, sunsets were renowned, toilets were scarce, summer does not always mean warmth, and without a pulse of hesitation, I think we would all agree to do it all over again… ■